.

.

University of California at Santa Cruz 1972-76, B.A. Earth Science, B.A. History, with Honors

Groundwater Committee, American Geophysical Union (1990 - Present)

Hlju6g!~~0_3.jpg) .

.

.

We're running a little behind on things,

but life is not always predictable, no matter what

the PLAN might have been. But as the bumper sticker says -

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED!

Indeed.

Here's part of an interview with a real professional

in our area talking about the issue, Dr. Fred Phillips.

We're doing this in segments, Part 2 will be up later.

Here's part of an interview with a real professional

in our area talking about the issue, Dr. Fred Phillips.

We're doing this in segments, Part 2 will be up later.

Statements from

AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. FRED PHILLIPS

Director of the Hydrology Program

Director of the Hydrology Program

New Mexico Tech

Socorro, New Mexico

Conducted early August, 2013

"First of all, the hydrology is not very well-defined,

out in the region where this is being proposed,

and the decisions that are made are in the frame

of reference of the policy of the state with regard to

water development, not so much in terms of

hydrological numbers."

"In my perspective, the San Augustin situation is a

classic natural resource conflict that

happens in the West....

and this has happened, time after time,

ever since the West was made part

of the United States."

.

.

"And the situation that keeps reoccurring,

is that natural resources in an area that are

valuable, for one reason or another -

in this particular case it's because New Mexico

has basically reached the limit of its water supply,

so any water that is used for new purposes has to be

redistributed from elsewhere -

and so the prospect of

a large supply of under-utilized water in the

San Augustin Basin is a great inducement.

.

.

And so people with money, with capital to spend,

have come in with the proposal that they lay claim to

that water, and then they export it,

and profit by doing so."

.

.

"When they do that, they come into conflict with

the local people, who live in the area - who feel

that they have some inherent right to that resource.

That's the underlying cause of conflict in the area"

.

"The developers there, the San Augustin Ranch,

are proposing to put in wells that are very deep,

and the number that I heard mentioned in the newspaper

and so on, was 3,000 feet deep, and they claim that

they will pump a confined aquifer that will have

minimum effects on the shallower aquifers,

which is where most of the local residents rely for

domestic water and water for livestock."

.

.

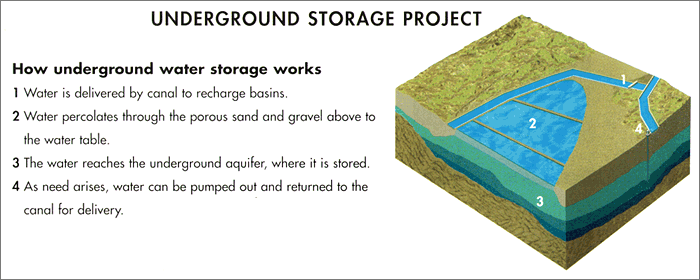

"They also claim that they are going to induce recharge

in some way, and this is not quite clear to me,

I have not seen the specifics on this, so I can't comment

very well on the merits of it,

but I have some inherent doubts about it....

because, the amount of time that's required for water

to reach the depths which they're proposing to pump

are very considerable, and studies haven't been done

on this, but if its typical of other basins in this part

of the country, that water at that depth, probably

recharged during the Pleistocene, during the last

ice age, more than 10,000 years ago, and the idea

that you could induce surface infiltration at the present

time and resupply that aquifer that is 3,000 feet deep,

is somewhat....it's difficult to envision how

that's going to work."

.

.

Interviewer: This claim that they can capture

all the rainfall that's being lost to evaporation seems

like an EXTREME concept, to put it mildly. I googled

and found that the way it's done is to somehow seal the

land - and that this has been done in parts

of north Africa and the Mideast.

What can you tell me here?

.

"What you are alluding to is what hydrologists call

the basin scale water balance.

So how much water falls on the basin is precipitation, right?

How much of it runs off, and how much of it infiltrates

to the groundwater - these are the critical numbers

that are involved.

And in this area, almost universally, the vast

majority of the water that falls on the land surface

is held in the soil, and then re-evaporates or is

transpired by plants back to the atmosphere."

.

.

"So, any water that runs off - the San Augustin Basin

is a closed basin - there's no outlet to the ocean,

so it runs down into the middle of the basin and then

it sinks down into the land. Whatever runs off

to the central playa, most of that becomes

groundwater recharge.

So, the only way to increase that groundwater

recharge is to reduce the amount that the plants

and the soil are using, and the standard method

for doing that - as you say - is to put some sort

of seal - asphalt, or plastic, or something, over the

land surface, so you collect all of the precipitation,

all of the rainfall, and you put it

into some central collection area where it then

infiltrates downward....and that's technically

feasible, but I have doubts as to whether converting

large areas of the landscape around the San Augustin Plains

to asphalt or something similar would be acceptable to

most people that live in the area."

.

.

.

What about the idea that if you seal it off....

well, isn't there a chance that funguses, microbes,

biological strangeness....that something, some

problem, could occur beneath the surface?

.

"Well, I think any 'biological strangeness' that

would be induced by putting a seal over the land

surface would be small in comparison to the

'biological strangeness' of denuding the landscape."

.

Then, of course, there's no opportunity for wildlife.

.

"That is correct, yes. Once you've removed all the vegetation,

then you've eliminated the ecosystem."

.

written all over it.

.

"I would say that there would be considerable

resistance to that idea."

.

.

That has aesthetic problemswritten all over it.

.

"I would say that there would be considerable

resistance to that idea."

.

.

Has it ever been done on a scale this large?

.

"Not that I'm aware of."

.

The things I read about in the Mideast

sounded much smaller.

.

"Yes. Typically, those are done on the scale of

individual farms, or small agricultural areas, where

several acres are devoted to precipitation collection

for every acre that's farmed, but we're talking

about the scale of an individual farm,

not a hydrological basin."

.

Is it a practical idea? Is it doable?

.

"In the sense of: are there insuperable technical

difficulties? No, certainly not. The main

difficulties are economic - is the value of the water

sufficient to get a return on investment,

if you have to make that much investment in infrastructure,

and they are social - the opposition of people

that live in the neighborhood."

.

.

They keep saying that they can do this without

water prices basically going up at all, but with

the huge investment they'll have....

it doesn't sound realistic.

.

"I'm reluctant to comment on that because I

certainly have not done any kind of cost/benefit study."

.

Well, they won't present a business plan.

.

"Right."

.

They're not saying what they'll charge for the water.

.

"Right. It's difficult for me to see how, at current

water prices , it could be economically feasible -

but without the specifics on the plan that's

difficult to evaluate."

.

.

In what you know about the history of water

issues moving through the New Mexico courts,

what are the possibilities here? Is the Appeals Court

likely to go either way, or....?

.

"I don't think that based on past precedent,

one can really make any prediction. In fact, if

you look at the history of recent important water

cases that have gone through the New Mexico courts,

they have frequently been reversed on appeal,

at various levels. So, there is not any highly consistent

pattern on controversial questions such as this.

Although there's obviously been major problems

and issues with the way that the plan has been

presented to the State Engineer, in that it resulted

in not being approved to date, there's nothing that

is inherently in conflict with the state constitution

and the water laws at a very blatant level.

These projects have been done in the past."

.

But nothing this large.

.

"Nothing this large, that is correct."

.

.

Can the people just look forward to more

and more corporations moving in and trying

to talk about moving water? Are we going

to see more and more of this?

.

"I think that that may depend in considerable part

on how things shake out with regard to

the San Augustin proposal."

.

(To be continued on a future post....)

.

*

Dr. Fred Phillips

Education

University of California at Santa Cruz 1972-76, B.A. Earth Science, B.A. History, with Honors

- University of Arizona, 1976-79; M.S. Hydrology

- University of Arizona, 1979-81; Ph.D. Hydrology

Positions

- 1981-1986, Assistant Professor of Hydrology, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro

- 1986-1991, Associate Professor of Hydrology

- 1991-present, Professor of Hydrology

- 1996-1999, Chair, Department of Earth and Environmental Science

- 1999-2001, Associate Chair, Department of Earth and Environmental Science

- 2005-present, Director of the Hydrology Program, New Mexico Tech

Professional Affiliations

- American Geophysical Union

- Geological Society of America

- American Quaternary Association

- Geochemical Society

- Sigma Xi

Professional Services

- Associate Editor, Water Resources Research (1989 - 1994)

Groundwater Committee, American Geophysical Union (1990 - Present)

- Co-Convenor, Penrose Conference "New Methods for Dating of Geomorphic Surfaces," Mammoth Lakes, California, 12-17 October, 1990

- NSF Graduate Fellowship Review Panel (1992 - 1993)

- National Research Council (National Academy of Science/Engineering)

- Committee on Technical Bases for Yucca Mountain Standards (1993 - 1995)

- Executive Committee, NSF-Funded Science & Technology Center on Sustainability of semiArid Hydrology and Riparian Areas (SAHRA) (2000 - present)

- O.E. Meinzer Award Committee, Hydrogeology Division, Geological Society of America (2001 - 2003)

- Hydrology Award Committee, Hydrology Section, American Geophysical Union (2002 - 2004)

- Director, Cosmic-Ray Produced Nuclide Systematics on Earth Project (CRONUS-Earth Project), an NSF-funded research consortium involving 14 research universities and other research institutions in the U.S. and abroad (2005 - present)

- Associate Editor, Quaternary Geochronology (2006-present)

Honors

- 1988: F.W. Clarke Medal, Geochemical Society

- 1989: New Mexico "Eminent Scholar" Award

- 1989: University of California at Santa Cruz "Alumnus of the Year" in Earth Sciences

- 1991: D. Foster Hewitt Lecturer, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

- 1994: Birdsall-Dreiss Distinguished Lecturer in Hydrogeology, Geological Society of America

- 1994: Distinguished Research Award, New Mexico Tech

- 2001: O.E. Meinzer Award (Hydrogeology), Geological Society of America

- 2003: Outstanding Teacher Award, Sigma Gamma Epsilon Chapter, New Mexico Tech

- 2005: Kirk Bryan Award, Geological Society of America (Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology Division)

- 2008: Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science

- 2008: Fellow, American Geophysical Union

Psalm 101:7

No one who practices deceit

shall dwell in my house;

no one who utters lies

shall continue before my eyes.

.

shall dwell in my house;

no one who utters lies

shall continue before my eyes.

.

Hlju6g!~~0_3.jpg) .

.

(Above - The date is 1902.)

Here's a petition to:

"Governor Susana Martinez: Make protecting New Mexico's

water a priority now!" on Change.org.

The New Mexico Environmental Law Center

(this is the outfit representing the people protesting the

water theft on the San Augustin Plains) has asked that this

petition be distributed. It's important. Here's the link:

.

http://www.change.org/petitions/governor-susana-martinez-make-protecting-new-mexico-s-water-a-priority-now?share_id=dQbLirBoST&utm_campaign=signature_receipt&utm_medium=email&utm_source=share_petition

Thanks!

.

petition be distributed. It's important. Here's the link:

.

http://www.change.org/petitions/governor-susana-martinez-make-protecting-new-mexico-s-water-a-priority-now?share_id=dQbLirBoST&utm_campaign=signature_receipt&utm_medium=email&utm_source=share_petition

Thanks!

.

.

The appeal/brief filed July 5 by the

Augustin Plains Ranch LLC with the

New Mexico Court of Appeals is viewable

via the link below.

As soon as the response from the

"good guys" attorney, Bruce Frederick,

.

Update - September 20, 9 AM

The briefs by the "good guys" got

filed September 13, and Carol Pittman sent us

this synopsis (thanks!). The brief filed by Bruce

Frederick for the "protestants" was joined

by two others in support of his arguments -

one by the State Engineer's Office and another

by attorney Peter White for the Cuchillo Valley

Community Ditch Association.

All three are on links below Carol's synopsis.

.

Three briefs were filed with the Court of Appeals on Friday, September 13, answering the “Brief in Chief” of the Augustin Plains Ranch. (Reminder: I sent you the summary of the APR filing on or about August 12, 2013 in case you want to review it.) One of the three briefs was filed by the State Engineer, one by Peter White on behalf of the Cuchillo Valley Community Ditch Association, and one by Bruce Frederick representing the protestants who are his clients.

I have extracted statements from Bruce Frederick’s brief to try to give you an idea of the arguments presented to the Court of Appeals. The statements are by no means exhaustive, only representative, but will give you a good idea of where we’ve been and where we’re going. Mr. Frederick has pointed out that the other two briefs are in support of his arguments.

Anyone who would like any or all of the complete briefs, please let me know and I will send whatever of those you request.

ARGUMENTS FROM THE BRIEF FILED BY BRUCE FREDERICK:

Nature of the Case. The district court upheld the state engineer's decision to deny APR's application for a permit to appropriate 54,000 acre-feet per year ("afy") of underground water via thirty-seven wells to be drilled on APR's extensive ranch in Catron County, New Mexico. ...

According to its application, APR desires to pump underground water from its ranch in Catron County to serve any future need for water that might arise in seven New Mexico counties, including irrigation, domestic, municipal, commercial, industrial, recreational, environmental, subdivision, replacement, and augmentation of surface flows in the Rio Grande. ... the application never discloses who specifically will use the water, what they will use it for, where they will use it, or how much water each user may require.

Course of Proceedings and Disposition before the Office of the state engineer. Protestants argued that APR's application provided only an open-ended list of potential places and purposes of use that might or might not occur within a vast area, and that it failed to specify how the total amount of water, 54,000 afy, would be allocated among the various places and purposes of use. Protestants claimed that this lack of specificity violated the prior appropriation doctrine, as codified in New Mexico's Constitution, statutes and regulations, and that it made effective public notice impossible to provide. APR filed a response brief but did not attach affidavits or otherwise clarify how and where it intended to use the tremendous amount of water it sought.

Synopsis of District Court’s Decision on Motion for Summary Judgment. The district court divided its analysis into three parts. In the first part, the court held that if APR's application failed to comply with New Mexico law, then the state engineer "was required to deny the application." In the second part, the court showed that APR's, application violated the statutory submission requirements ... and therefore, the application failed to comply with law and thus exceeded the state engineer's statutory authority to consider or approve. In the third part of its analysis, the court showed that APR's application also "contradicts beneficial use as the basis of a water right and public ownership of water, as declared in the New Mexico Constitution.” Based on its three-part analysis, ... the district court entered an order upholding the state engineer's decision to deny APR's application.

... the court concluded that Section 72-12-3 requires applicants to disclose a present intention to appropriate water in a specific amount, for a specific purpose, and in a specific place.

The district court observed: Applicant's claim over water, in the amount of 54,000 afy, is larger than the maximum water supply available for the Carlsbad Irrigation District's many users. This illustration from one watershed demonstrates the enormous potential available for Applicant to monopolize the waters that would have otherwise been available to other users wishing to apply the underground waters of the San Agustin Basin to beneficial use. ... In reviewing the application in light of the permitting statute's language, context, history and purpose, there is no genuine issue of material fact as to the application's invalidity regarding purpose and place of use. ... With no details for all of the required elements of a water permit, the State Engineer could not perform his statutory duties ... of determining whether the proposed appropriation would impair existing rights, be contrary to the conservation of water, or be detrimental to the public welfare. As a matter of law, the State Engineer could not allow an applicant to hold up other uses of water under the doctrine of relation, when the applicant broadly claims a huge amount of water for any use and generalizes as its place of use "any area" in seven counties in the Middle Rio Grande Basin, covering many thousands of square miles.

APR Received a Pre-Decision Hearing That Complied With the Governing Statutes, and it is not Entitled to an “Evidentiary” Hearing on a Legally Invalid Application. The first indication that the governing statutes do not grant APR an absolute right to an evidentiary hearing is the fact that these words, "evidentiary hearing," never appear in the statutes.

... the error of OSE staff in accepting APR's application does not prevent Protestants from pointing out the error and seeking dismissal in accordance with law. Protestants' statutory rights of due process are equal to those of APR ...

The District Court’s Judgment Should be Upheld, Because APR’s Application is Legally Invalid on its Face as a Matter of Law. APR's application seeks authorization (1) to pump 54,000 afy of groundwater, (2) for use in an area comprising tens of thousands of square miles, (3) to serve any conceivable purpose that might arise. APR admits that it does not know how, when, how much, or by whom water will actually be used at any particular location.

APR's application designates seven counties where water might be used. As the district court pointed out, APR's unclear intentions may explain the absurdly large number of objectors-over 900. On the other hand, others likely failed to object because they could not determine from the public notice exactly what APR has in mind.

PLEASE NOTE: There may or may not be a hearing. The Appeals Court can decide the case based on briefs only. Bruce has indicated in his brief that he’d like to have a hearing.

.The briefs by the "good guys" got

filed September 13, and Carol Pittman sent us

this synopsis (thanks!). The brief filed by Bruce

Frederick for the "protestants" was joined

by two others in support of his arguments -

one by the State Engineer's Office and another

by attorney Peter White for the Cuchillo Valley

Community Ditch Association.

All three are on links below Carol's synopsis.

.

Three briefs were filed with the Court of Appeals on Friday, September 13, answering the “Brief in Chief” of the Augustin Plains Ranch. (Reminder: I sent you the summary of the APR filing on or about August 12, 2013 in case you want to review it.) One of the three briefs was filed by the State Engineer, one by Peter White on behalf of the Cuchillo Valley Community Ditch Association, and one by Bruce Frederick representing the protestants who are his clients.

I have extracted statements from Bruce Frederick’s brief to try to give you an idea of the arguments presented to the Court of Appeals. The statements are by no means exhaustive, only representative, but will give you a good idea of where we’ve been and where we’re going. Mr. Frederick has pointed out that the other two briefs are in support of his arguments.

Anyone who would like any or all of the complete briefs, please let me know and I will send whatever of those you request.

ARGUMENTS FROM THE BRIEF FILED BY BRUCE FREDERICK:

Nature of the Case. The district court upheld the state engineer's decision to deny APR's application for a permit to appropriate 54,000 acre-feet per year ("afy") of underground water via thirty-seven wells to be drilled on APR's extensive ranch in Catron County, New Mexico. ...

According to its application, APR desires to pump underground water from its ranch in Catron County to serve any future need for water that might arise in seven New Mexico counties, including irrigation, domestic, municipal, commercial, industrial, recreational, environmental, subdivision, replacement, and augmentation of surface flows in the Rio Grande. ... the application never discloses who specifically will use the water, what they will use it for, where they will use it, or how much water each user may require.

Course of Proceedings and Disposition before the Office of the state engineer. Protestants argued that APR's application provided only an open-ended list of potential places and purposes of use that might or might not occur within a vast area, and that it failed to specify how the total amount of water, 54,000 afy, would be allocated among the various places and purposes of use. Protestants claimed that this lack of specificity violated the prior appropriation doctrine, as codified in New Mexico's Constitution, statutes and regulations, and that it made effective public notice impossible to provide. APR filed a response brief but did not attach affidavits or otherwise clarify how and where it intended to use the tremendous amount of water it sought.

Synopsis of District Court’s Decision on Motion for Summary Judgment. The district court divided its analysis into three parts. In the first part, the court held that if APR's application failed to comply with New Mexico law, then the state engineer "was required to deny the application." In the second part, the court showed that APR's, application violated the statutory submission requirements ... and therefore, the application failed to comply with law and thus exceeded the state engineer's statutory authority to consider or approve. In the third part of its analysis, the court showed that APR's application also "contradicts beneficial use as the basis of a water right and public ownership of water, as declared in the New Mexico Constitution.” Based on its three-part analysis, ... the district court entered an order upholding the state engineer's decision to deny APR's application.

... the court concluded that Section 72-12-3 requires applicants to disclose a present intention to appropriate water in a specific amount, for a specific purpose, and in a specific place.

The district court observed: Applicant's claim over water, in the amount of 54,000 afy, is larger than the maximum water supply available for the Carlsbad Irrigation District's many users. This illustration from one watershed demonstrates the enormous potential available for Applicant to monopolize the waters that would have otherwise been available to other users wishing to apply the underground waters of the San Agustin Basin to beneficial use. ... In reviewing the application in light of the permitting statute's language, context, history and purpose, there is no genuine issue of material fact as to the application's invalidity regarding purpose and place of use. ... With no details for all of the required elements of a water permit, the State Engineer could not perform his statutory duties ... of determining whether the proposed appropriation would impair existing rights, be contrary to the conservation of water, or be detrimental to the public welfare. As a matter of law, the State Engineer could not allow an applicant to hold up other uses of water under the doctrine of relation, when the applicant broadly claims a huge amount of water for any use and generalizes as its place of use "any area" in seven counties in the Middle Rio Grande Basin, covering many thousands of square miles.

APR Received a Pre-Decision Hearing That Complied With the Governing Statutes, and it is not Entitled to an “Evidentiary” Hearing on a Legally Invalid Application. The first indication that the governing statutes do not grant APR an absolute right to an evidentiary hearing is the fact that these words, "evidentiary hearing," never appear in the statutes.

... the error of OSE staff in accepting APR's application does not prevent Protestants from pointing out the error and seeking dismissal in accordance with law. Protestants' statutory rights of due process are equal to those of APR ...

The District Court’s Judgment Should be Upheld, Because APR’s Application is Legally Invalid on its Face as a Matter of Law. APR's application seeks authorization (1) to pump 54,000 afy of groundwater, (2) for use in an area comprising tens of thousands of square miles, (3) to serve any conceivable purpose that might arise. APR admits that it does not know how, when, how much, or by whom water will actually be used at any particular location.

APR's application designates seven counties where water might be used. As the district court pointed out, APR's unclear intentions may explain the absurdly large number of objectors-over 900. On the other hand, others likely failed to object because they could not determine from the public notice exactly what APR has in mind.

PLEASE NOTE: There may or may not be a hearing. The Appeals Court can decide the case based on briefs only. Bruce has indicated in his brief that he’d like to have a hearing.

Here's the complete brief filed by Bruce Fredrick:

.

.

Here's the complete brief filed by the State Engineer:

.

.

Lastly, here's the complete brief from the Cuchillo Valley folks:

http://maninthemaze.com/images/Filed_Answer_Brief_-_Peter_White_9.13.13.pdf

.

Lastly, here's the complete brief from the Cuchillo Valley folks:

http://maninthemaze.com/images/Filed_Answer_Brief_-_Peter_White_9.13.13.pdf

.

.jpg)

.jpg)